Introduction

Distance measures are fundamental to many FDA methods including clustering, k-nearest neighbors regression, and outlier detection. fdars provides both true metrics (satisfying the triangle inequality) and semimetrics (which may not).

A metric on a space satisfies:

- (non-negativity)

- (identity of indiscernibles)

- (symmetry)

- (triangle inequality)

A semimetric satisfies only conditions 1-3.

library(fdars)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'fdars'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> cov, decompose, deriv, median, sd, var

#> The following object is masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> norm

library(ggplot2)

theme_set(theme_minimal())

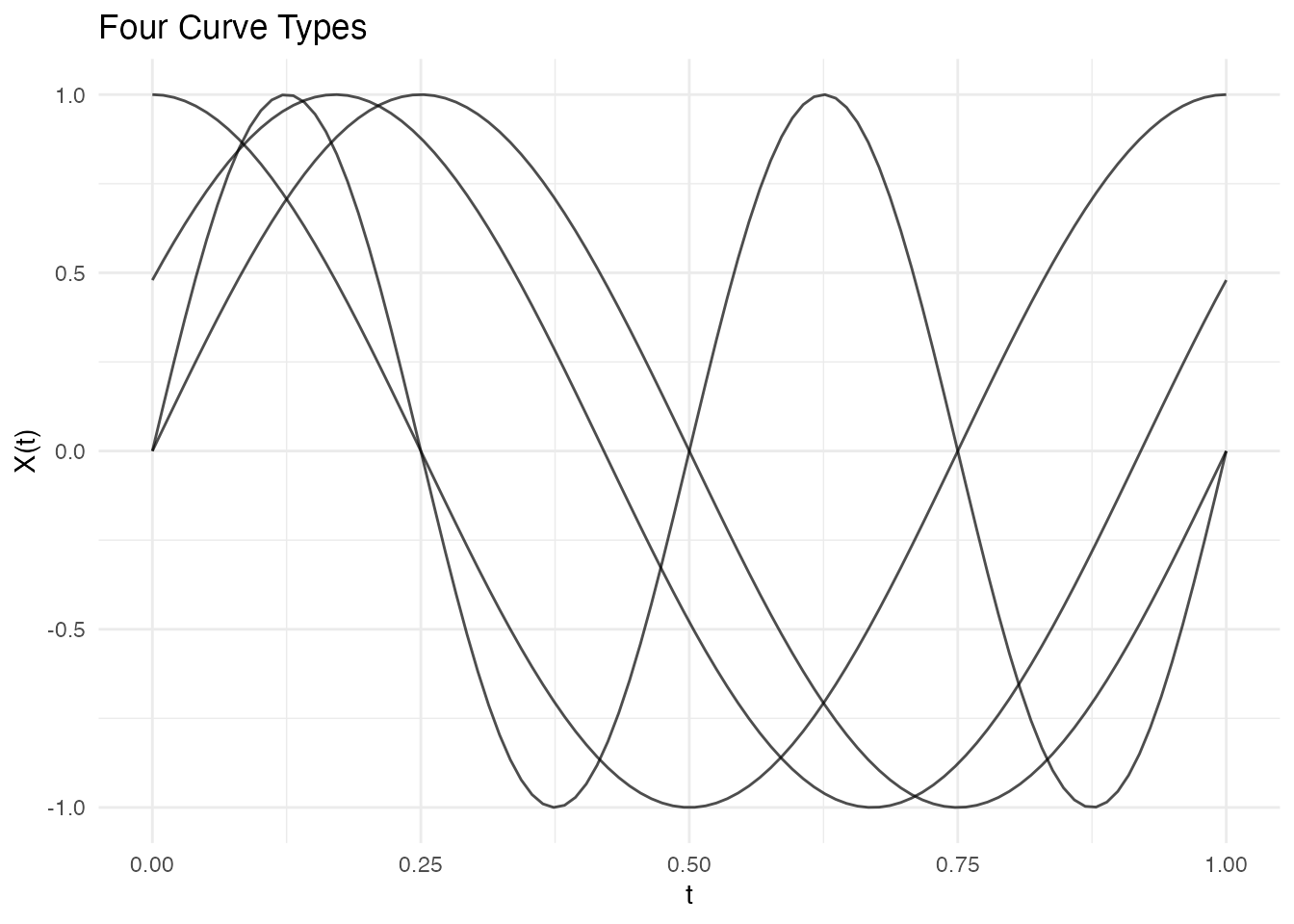

# Create example data with different curve types

set.seed(42)

m <- 100

t_grid <- seq(0, 1, length.out = m)

# Four types of curves

curve1 <- sin(2 * pi * t_grid) # Sine

curve2 <- sin(2 * pi * t_grid + 0.5) # Phase-shifted sine

curve3 <- cos(2 * pi * t_grid) # Cosine

curve4 <- sin(4 * pi * t_grid) # Higher frequency

X <- rbind(curve1, curve2, curve3, curve4)

fd <- fdata(X, argvals = t_grid,

names = list(main = "Four Curve Types"))

plot(fd)

True Metrics

Lp Distance (metric.lp)

The distance is the most common choice for functional data. It computes the integrated norm of the difference between two functions:

For discrete observations, this is approximated using numerical integration (Simpson’s rule):

where are quadrature weights.

Special cases:

- (L2/Euclidean): Most common, corresponds to the standard functional norm. Sensitive to vertical differences.

- (L1/Manhattan): More robust to outliers than L2.

- (L-infinity/Chebyshev): Maximum absolute difference, .

# L2 (Euclidean) distance - default

dist_l2 <- metric.lp(fd)

print(round(as.matrix(dist_l2), 3))

#> curve1 curve2 curve3 curve4

#> curve1 0.00 0.350 1.000 1

#> curve2 0.35 0.000 0.722 1

#> curve3 1.00 0.722 0.000 1

#> curve4 1.00 1.000 1.000 0

# L1 (Manhattan) distance

dist_l1 <- metric.lp(fd, lp = 1)

# L-infinity (maximum) distance

dist_linf <- metric.lp(fd, lp = Inf)Weighted Lp Distance

Apply different weights to different parts of the domain:

This is useful when certain parts of the domain are more important than others.

Hausdorff Distance (metric.hausdorff)

The Hausdorff distance treats curves as sets of points in 2D space and computes the maximum of minimum distances:

where is the point on the graph of at time .

The Hausdorff distance is useful when:

- Curves may cross each other

- The timing of features is less important than their shape

- Comparing curves with different supports

dist_haus <- metric.hausdorff(fd)

print(round(as.matrix(dist_haus), 3))

#> curve1 curve2 curve3 curve4

#> curve1 0.000 0.479 0.678 0.328

#> curve2 0.479 0.000 0.521 0.416

#> curve3 0.678 0.521 0.000 0.352

#> curve4 0.328 0.416 0.352 0.000Dynamic Time Warping (metric.DTW)

DTW allows for non-linear alignment of curves before computing the distance. It finds the optimal warping path that minimizes:

subject to boundary conditions, monotonicity, and continuity constraints.

The Sakoe-Chiba band constraint limits the warping to , preventing excessive distortion:

DTW is particularly effective for:

- Phase-shifted signals

- Time series with varying speed

- Comparing signals with local time distortions

dist_dtw <- metric.DTW(fd)

print(round(as.matrix(dist_dtw), 3))

#> curve1 curve2 curve3 curve4

#> curve1 0.000 1.452 18.185 24.844

#> curve2 1.452 0.000 3.488 25.980

#> curve3 18.185 3.488 0.000 40.825

#> curve4 24.844 25.980 40.825 0.000Notice that DTW gives a smaller distance between the original sine and phase-shifted sine compared to L2, because it can align them:

# Compare L2 vs DTW for phase-shifted curves

cat("L2 distance (sine vs phase-shifted):", round(as.matrix(dist_l2)[1, 2], 3), "\n")

#> L2 distance (sine vs phase-shifted): 0.35

cat("DTW distance (sine vs phase-shifted):", round(as.matrix(dist_dtw)[1, 2], 3), "\n")

#> DTW distance (sine vs phase-shifted): 1.452DTW with band constraint:

# Restrict warping to 10% of the series length

dist_dtw_band <- metric.DTW(fd, w = round(m * 0.1))Kullback-Leibler Divergence (metric.kl)

The symmetric Kullback-Leibler divergence treats normalized curves as probability density functions:

Before computing, curves are shifted to be non-negative and normalized to integrate to 1:

This metric is useful for:

- Comparing density-like functions

- Distribution comparison

- Information-theoretic analysis

# Shift curves to be positive for KL

X_pos <- X - min(X) + 0.1

fd_pos <- fdata(X_pos, argvals = t_grid)

dist_kl <- metric.kl(fd_pos)

print(round(as.matrix(dist_kl), 3))

#> curve1 curve2 curve3 curve4

#> curve1 0.000 0.139 1.208 1.187

#> curve2 0.139 0.000 0.630 1.426

#> curve3 1.208 0.630 0.000 1.156

#> curve4 1.187 1.426 1.156 0.000Semimetrics

Semimetrics may not satisfy the triangle inequality but can be more appropriate for certain applications or provide computational advantages.

PCA-Based Semimetric (semimetric.pca)

Projects curves onto the first principal components and computes the Euclidean distance in the reduced space:

where is the -th principal component score of , and are the eigenfunctions from functional PCA.

This semimetric is useful for:

- Dimension reduction before distance computation

- Noise reduction (low-rank approximation)

- Computational efficiency with many evaluation points

# Distance using first 3 PCs

dist_pca <- semimetric.pca(fd, ncomp = 3)

print(round(as.matrix(dist_pca), 3))

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 0.000 3.514 10.000 9.950

#> [2,] 3.514 0.000 7.198 9.961

#> [3,] 10.000 7.198 0.000 10.000

#> [4,] 9.950 9.961 10.000 0.000Derivative-Based Semimetric (semimetric.deriv)

Computes the distance based on the -th derivative of the curves:

where denotes the -th derivative of .

This semimetric focuses on the shape and dynamics of curves rather than their absolute values. It is particularly useful when:

- Comparing rate of change (first derivative)

- Analyzing curvature (second derivative)

- Functions are measured with different baselines

# First derivative (velocity)

dist_deriv1 <- semimetric.deriv(fd, nderiv = 1)

# Second derivative (acceleration/curvature)

dist_deriv2 <- semimetric.deriv(fd, nderiv = 2)

cat("First derivative distances:\n")

#> First derivative distances:

print(round(as.matrix(dist_deriv1), 3))

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 0.000 2.197 6.279 9.912

#> [2,] 2.197 0.000 4.530 9.912

#> [3,] 6.279 4.530 0.000 9.912

#> [4,] 9.912 9.912 9.912 0.000Basis Semimetric (semimetric.basis)

Projects curves onto a basis (B-spline or Fourier) and computes the Euclidean distance between the coefficient vectors:

where are the basis coefficients from .

For B-splines: Local support provides good approximation of local features.

For Fourier basis: Global support captures periodic patterns efficiently.

# B-spline basis (local features)

dist_bspline <- semimetric.basis(fd, nbasis = 15, basis = "bspline")

# Fourier basis (periodic patterns)

dist_fourier <- semimetric.basis(fd, nbasis = 11, basis = "fourier")

cat("B-spline basis distances:\n")

#> B-spline basis distances:

print(round(as.matrix(dist_bspline), 3))

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 0.000 1.509 4.015 3.913

#> [2,] 1.509 0.000 2.771 3.999

#> [3,] 4.015 2.771 0.000 4.289

#> [4,] 3.913 3.999 4.289 0.000Fourier Semimetric (semimetric.fourier)

Uses the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to compute Fourier coefficients and measures distance based on the first frequency components:

where is the -th Fourier coefficient computed via FFT.

This is computationally efficient for large datasets and particularly useful for periodic or frequency-domain analysis.

dist_fft <- semimetric.fourier(fd, nfreq = 5)

cat("Fourier (FFT) distances:\n")

#> Fourier (FFT) distances:

print(round(as.matrix(dist_fft), 3))

#> curve1 curve2 curve3 curve4

#> curve1 0.000 0.005 0.012 0.694

#> curve2 0.005 0.000 0.008 0.695

#> curve3 0.012 0.008 0.000 0.700

#> curve4 0.694 0.695 0.700 0.000Horizontal Shift Semimetric (semimetric.hshift)

Finds the optimal horizontal shift before computing the distance:

where is the shift in discrete time units and is the maximum allowed shift.

This semimetric is simpler than DTW (only horizontal shifts, no warping) but can be very effective for:

- Phase-shifted periodic signals

- ECG or other physiological signals with timing variations

- Comparing curves where horizontal alignment is meaningful

dist_hshift <- semimetric.hshift(fd)

cat("Horizontal shift distances:\n")

#> Horizontal shift distances:

print(round(as.matrix(dist_hshift), 3))

#> curve1 curve2 curve3 curve4

#> curve1 0.000 0.005 0.010 0.733

#> curve2 0.005 0.000 0.005 0.629

#> curve3 0.010 0.005 0.000 0.718

#> curve4 0.733 0.629 0.718 0.000Unified Interface

Use metric() for a unified interface to all distance

functions:

Comparing Distance Measures

Different distance measures capture different aspects of curve similarity:

# Create comparison data

dists <- list(

L2 = as.vector(as.matrix(dist_l2)),

L1 = as.vector(as.matrix(dist_l1)),

DTW = as.vector(as.matrix(dist_dtw)),

Hausdorff = as.vector(as.matrix(dist_haus))

)

# Correlation between distance measures

dist_mat <- do.call(cbind, dists)

cat("Correlation between distance measures:\n")

#> Correlation between distance measures:

print(round(cor(dist_mat), 2))

#> L2 L1 DTW Hausdorff

#> L2 1.00 1.00 0.82 0.74

#> L1 1.00 1.00 0.82 0.74

#> DTW 0.82 0.82 1.00 0.32

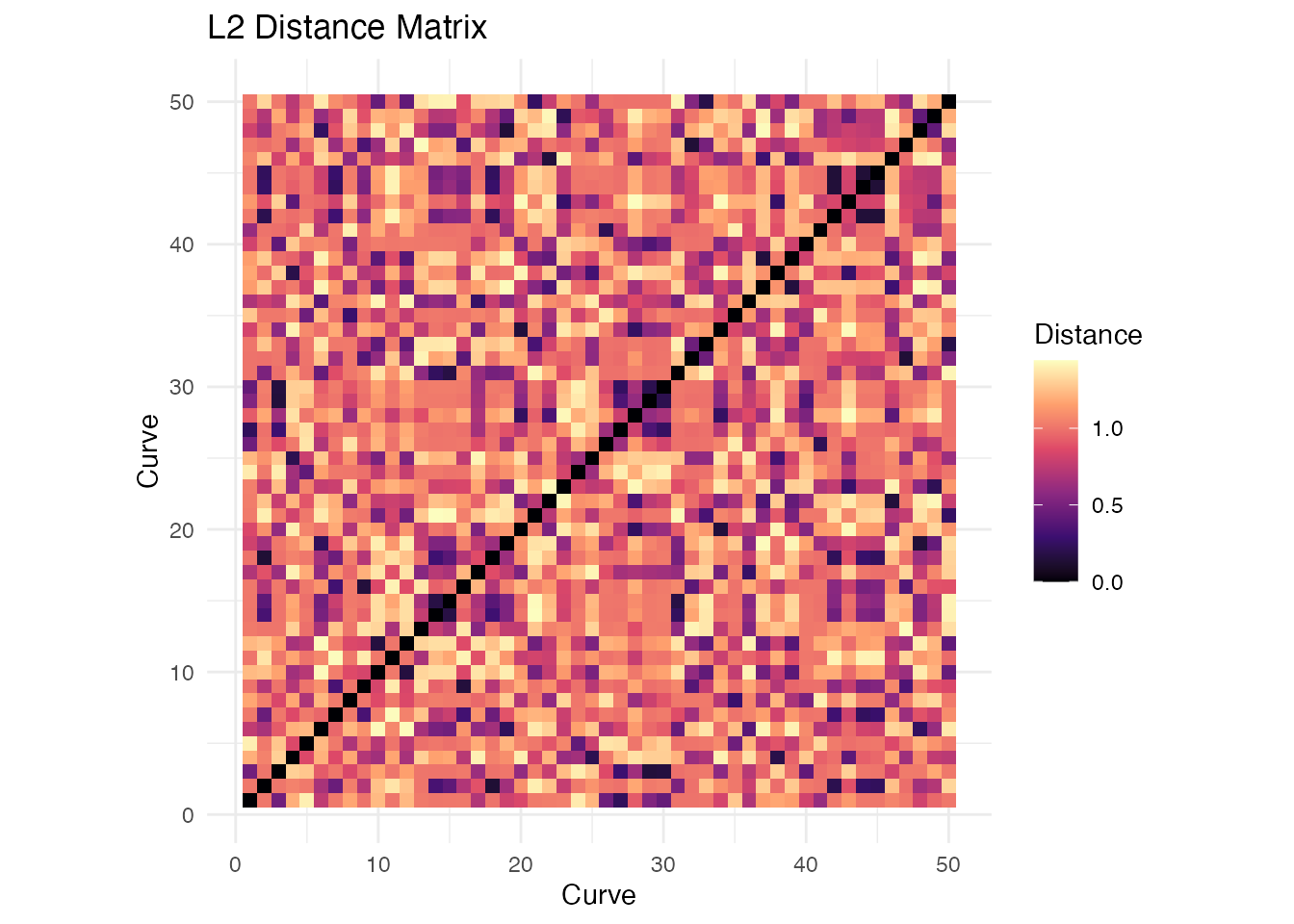

#> Hausdorff 0.74 0.74 0.32 1.00Distance Matrices for Larger Samples

# Generate larger sample

set.seed(123)

n <- 50

X_large <- matrix(0, n, m)

for (i in 1:n) {

phase <- runif(1, 0, 2*pi)

freq <- sample(1:3, 1)

X_large[i, ] <- sin(freq * pi * t_grid + phase) + rnorm(m, sd = 0.1)

}

fd_large <- fdata(X_large, argvals = t_grid)

# Compute distance matrix

dist_matrix <- metric.lp(fd_large)

# Visualize as heatmap using ggplot2

dist_df <- expand.grid(Curve1 = 1:n, Curve2 = 1:n)

dist_df$Distance <- as.vector(as.matrix(dist_matrix))

ggplot(dist_df, aes(x = Curve1, y = Curve2, fill = Distance)) +

geom_tile() +

scale_fill_viridis_c(option = "magma") +

coord_equal() +

labs(x = "Curve", y = "Curve", title = "L2 Distance Matrix") +

theme_minimal()

Metric Properties Summary

| Distance | Type | Triangle Ineq. | Phase Invariant | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lp | Metric | Yes | No | O(nm) |

| Hausdorff | Metric | Yes | Partial | O(nm²) |

| DTW | Metric* | Yes* | Yes | O(nm²) |

| KL | Semimetric | No | No | O(nm) |

| PCA | Semimetric | Yes** | No | O(nm + nq²) |

| Derivative | Semimetric | Yes** | No | O(nm) |

| Basis | Semimetric | Yes** | No | O(nmK) |

| Fourier | Semimetric | Yes** | No | O(nm log m) |

| H-shift | Semimetric | No | Yes | O(nm·h_max) |

* DTW satisfies triangle inequality when using the same warping path ** These satisfy triangle inequality in the reduced/transformed space

Choosing a Distance Measure

| Scenario | Recommended Distance |

|---|---|

| General purpose | L2 (metric.lp) |

| Heavy-tailed noise | L1 (metric.lp, p=1) |

| Worst-case analysis | L-infinity (metric.lp, p=Inf) |

| Phase-shifted signals | DTW or H-shift |

| Curves that cross | Hausdorff |

| High-dimensional data | PCA-based |

| Shape comparison | Derivative-based |

| Periodic data | Fourier-based |

| Density-like curves | Kullback-Leibler |

Performance

Distance computations are parallelized in Rust:

# Benchmark for 500 curves

X_bench <- matrix(rnorm(500 * 200), 500, 200)

fd_bench <- fdata(X_bench)

system.time(metric.lp(fd_bench))

#> user system elapsed

#> 0.089 0.000 0.045

system.time(metric.DTW(fd_bench))

#> user system elapsed

#> 1.234 0.000 0.312Using Distances in Other Methods

Distance functions can be passed to clustering and regression:

# K-means with L1 distance

km_l1 <- cluster.kmeans(fd_large, ncl = 3, metric = "L1", seed = 42)

# K-means with custom metric function

km_dtw <- cluster.kmeans(fd_large, ncl = 3, metric = metric.DTW, seed = 42)

# Nonparametric regression uses distances internally

y <- rnorm(n)

fit_np <- fregre.np(fd_large, y, metric = metric.lp)References

- Berndt, D.J. and Clifford, J. (1994). Using Dynamic Time Warping to Find Patterns in Time Series. KDD Workshop, 359-370.

- Ferraty, F. and Vieu, P. (2006). Nonparametric Functional Data Analysis. Springer.

- Ramsay, J.O. and Silverman, B.W. (2005). Functional Data Analysis. Springer, 2nd edition.

- Sakoe, H. and Chiba, S. (1978). Dynamic programming algorithm optimization for spoken word recognition. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 26(1), 43-49.