Introduction

Functional regression extends classical regression to handle functional predictors or responses. The most common setting is scalar-on-function regression, where a scalar response is predicted from a functional predictor .

The Functional Linear Model

The foundational model in functional regression is the functional linear model:

where:

- is the scalar response for observation

- is the functional predictor observed over domain

- is the intercept

- is the coefficient function (unknown, to be estimated)

- are i.i.d. errors

The integral can be interpreted as a weighted average of the functional predictor, where determines the importance of each time point in predicting .

The Estimation Challenge

Unlike classical regression where we estimate a finite number of parameters, here we must estimate an entire function . This is an ill-posed inverse problem: infinitely many solutions may exist, and small changes in the data can lead to large changes in the estimate.

fdars provides three main approaches to regularize this problem:

-

Principal Component Regression

(

fregre.pc) — dimension reduction via FPCA -

Basis Expansion Regression

(

fregre.basis) — represent in a finite basis -

Nonparametric Regression (

fregre.np) — make no parametric assumptions

library(fdars)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'fdars'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> cov, decompose, deriv, median, sd, var

#> The following object is masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> norm

library(ggplot2)

theme_set(theme_minimal())

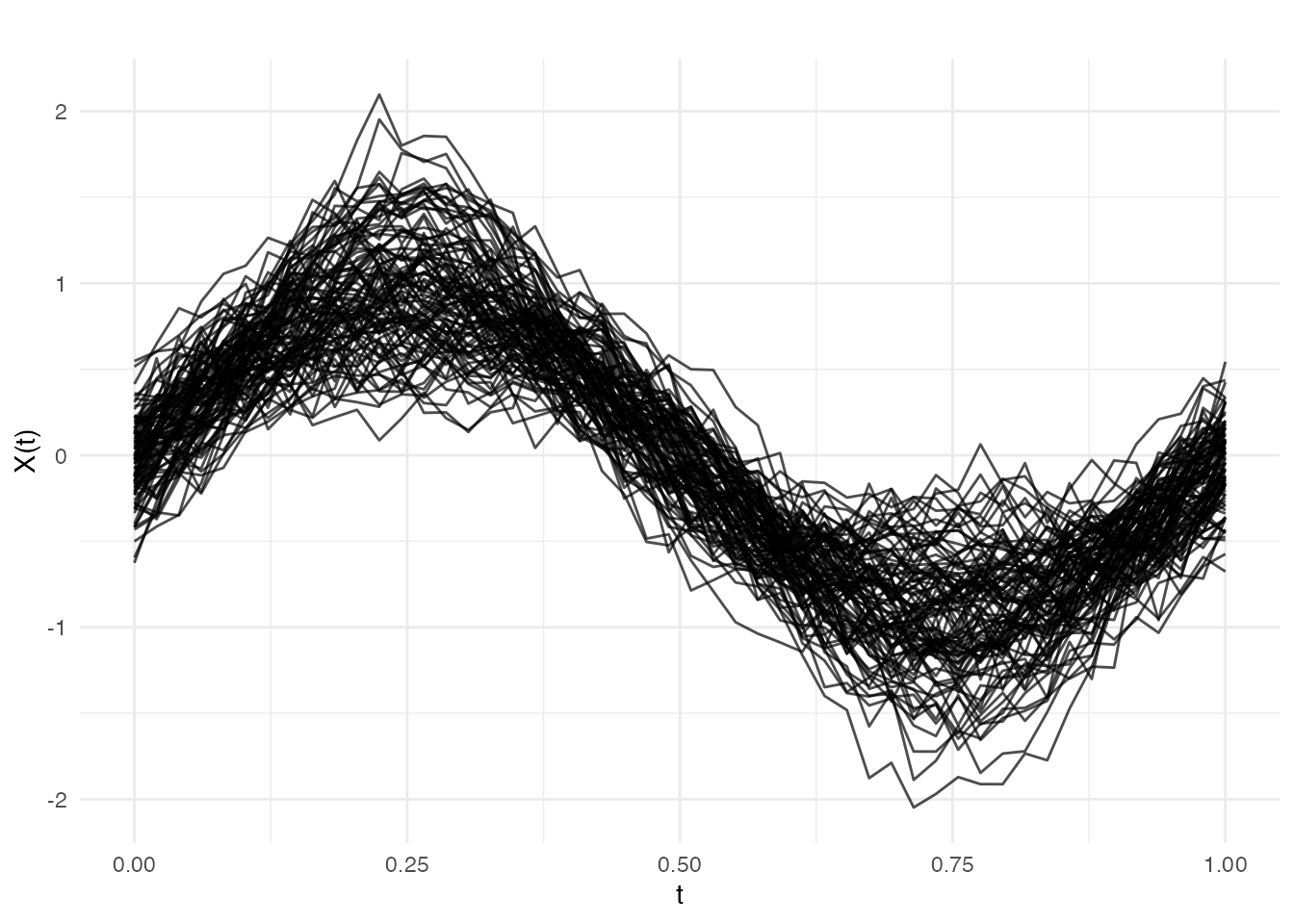

# Generate example data

set.seed(42)

n <- 100

m <- 50

t_grid <- seq(0, 1, length.out = m)

# Functional predictors

X <- matrix(0, n, m)

for (i in 1:n) {

X[i, ] <- sin(2 * pi * t_grid) * rnorm(1, 1, 0.3) +

cos(4 * pi * t_grid) * rnorm(1, 0, 0.2) +

rnorm(m, sd = 0.1)

}

fd <- fdata(X, argvals = t_grid)

# True coefficient function

beta_true <- sin(2 * pi * t_grid)

# Generate response: Y = integral(beta * X) + noise

y <- numeric(n)

for (i in 1:n) {

y[i] <- sum(beta_true * X[i, ]) / m + rnorm(1, sd = 0.5)

}

plot(fd)

Principal Component Regression

Principal component regression (PCR) reduces the infinite-dimensional problem to a finite-dimensional one by projecting the functional data onto its principal components.

Mathematical Formulation

Using functional principal component analysis (FPCA), each curve can be represented as:

where are the eigenfunctions (principal components) and are the PC scores.

Truncating at components and substituting into the functional linear model gives:

where . This is now a standard multiple linear regression with predictors .

The coefficient function is reconstructed as:

Choosing the Number of Components

The key tuning parameter is , the number of principal components:

- Too few: underfitting, missing important variation in

- Too many: overfitting, including noise components

Cross-validation or information criteria (AIC, BIC) can guide the choice.

Cross-Validation for Component Selection

# Find optimal number of components

cv_pc <- fregre.pc.cv(fd, y, kmax = 10)

cat("Optimal number of components:", cv_pc$ncomp.opt, "\n")

#> Optimal number of components:

cat("CV error by component:\n")

#> CV error by component:

print(round(cv_pc$cv.error, 4))

#> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

#> 0.2674 0.2700 0.2720 0.2735 0.2785 0.2735 0.2691 0.2718 0.2728 0.2744 0.2735

#> 12 13 14 15

#> 0.2746 0.2714 0.2703 0.2746Prediction

# Split data

train_idx <- 1:80

test_idx <- 81:100

fd_train <- fd[train_idx, ]

fd_test <- fd[test_idx, ]

y_train <- y[train_idx]

y_test <- y[test_idx]

# Fit on training data

fit_train <- fregre.pc(fd_train, y_train, ncomp = 3)

# Predict on test data

y_pred <- predict(fit_train, fd_test)

# Evaluate

cat("Test RMSE:", round(pred.RMSE(y_test, y_pred), 3), "\n")

#> Test RMSE: 0.457

cat("Test R2:", round(pred.R2(y_test, y_pred), 3), "\n")

#> Test R2: 0.219Basis Expansion Regression

Basis expansion regression represents both the functional predictor and the coefficient function using a finite set of basis functions, reducing the infinite-dimensional problem to a finite-dimensional one.

Mathematical Formulation

Let be a set of basis functions (e.g., B-splines or Fourier). We expand:

Substituting into the functional linear model:

This simplifies to:

where are the basis coefficients of , are the unknown coefficients of , and is the inner product matrix with entries .

Ridge Regularization

To prevent overfitting (especially with many basis functions), we add a roughness penalty. The penalized least squares objective is:

The penalty discourages rapid oscillations. In matrix form:

where is the roughness penalty matrix with .

The solution is:

Basis Choice

- B-splines: Flexible, local support, good for non-periodic data

- Fourier: Natural for periodic data, global support

Basic Usage

# Fit basis regression with 15 B-spline basis functions

fit_basis <- fregre.basis(fd, y, nbasis = 15, type = "bspline")

print(fit_basis)

#> Functional regression model

#> Number of observations: 100

#> R-squared: 0.5805754Regularization

The lambda parameter controls regularization:

# Higher lambda = more regularization

fit_basis_reg <- fregre.basis(fd, y, nbasis = 15, type = "bspline", lambda = 1)Cross-Validation for Lambda

# Find optimal lambda

cv_basis <- fregre.basis.cv(fd, y, nbasis = 15, type = "bspline",

lambda = c(0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10))

cat("Optimal lambda:", cv_basis$lambda.opt, "\n")

#> Optimal lambda:

cat("CV error by lambda:\n")

#> CV error by lambda:

print(round(cv_basis$cv.error, 4))

#> 0 0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10

#> 0.5967 0.5926 0.5605 0.4299 0.3209 0.2977Fourier Basis

For periodic data, use Fourier basis:

fit_fourier <- fregre.basis(fd, y, nbasis = 11, type = "fourier")Nonparametric Regression

Nonparametric functional regression makes no parametric assumptions about the relationship between and . Instead, it estimates directly using local averaging techniques.

The General Framework

Given a new functional observation , the predicted response is:

where are weights that depend on the “distance” between and the training curves . Different methods define these weights differently.

Functional Distance

A key component is the semimetric measuring similarity between curves. Common choices:

- metric:

- metric:

- PCA-based semimetric: using PC scores

Nadaraya-Watson Estimator

The Nadaraya-Watson (kernel regression) estimator uses:

where is a kernel function and is the bandwidth controlling the smoothness:

- Small : weights concentrated on nearest neighbors (low bias, high variance)

- Large : weights spread across many observations (high bias, low variance)

Common kernels include:

| Kernel | Formula |

|---|---|

| Gaussian | |

| Epanechnikov | |

| Uniform |

k-Nearest Neighbors

The k-NN estimator averages the responses of the closest curves:

where is the set of indices of the nearest neighbors of .

Two variants are available:

-

Global k-NN (

kNN.gCV): single selected by leave-one-out cross-validation -

Local k-NN (

kNN.lCV): adaptive that may vary per prediction point

Bandwidth Selection

# Cross-validation for bandwidth

cv_np <- fregre.np.cv(fd, y, h.seq = seq(0.1, 1, by = 0.1))

cat("Optimal bandwidth:", cv_np$h.opt, "\n")

#> Optimal bandwidth:Different Kernels

# Epanechnikov kernel

fit_epa <- fregre.np(fd, y, Ker = "epa")

# Available kernels: "norm", "epa", "tri", "quar", "cos", "unif"Comparing Methods

# Fit all methods on training data

fit1 <- fregre.pc(fd_train, y_train, ncomp = 3)

fit2 <- fregre.basis(fd_train, y_train, nbasis = 15)

fit3 <- fregre.np(fd_train, y_train, type.S = "kNN.gCV")

# Predict on test data

pred1 <- predict(fit1, fd_test)

pred2 <- predict(fit2, fd_test)

pred3 <- predict(fit3, fd_test)

# Compare performance

results <- data.frame(

Method = c("PC Regression", "Basis Regression", "k-NN"),

RMSE = c(pred.RMSE(y_test, pred1),

pred.RMSE(y_test, pred2),

pred.RMSE(y_test, pred3)),

R2 = c(pred.R2(y_test, pred1),

pred.R2(y_test, pred2),

pred.R2(y_test, pred3))

)

print(results)

#> Method RMSE R2

#> 1 PC Regression 0.4570245 0.21884391

#> 2 Basis Regression 0.8989962 -2.02255778

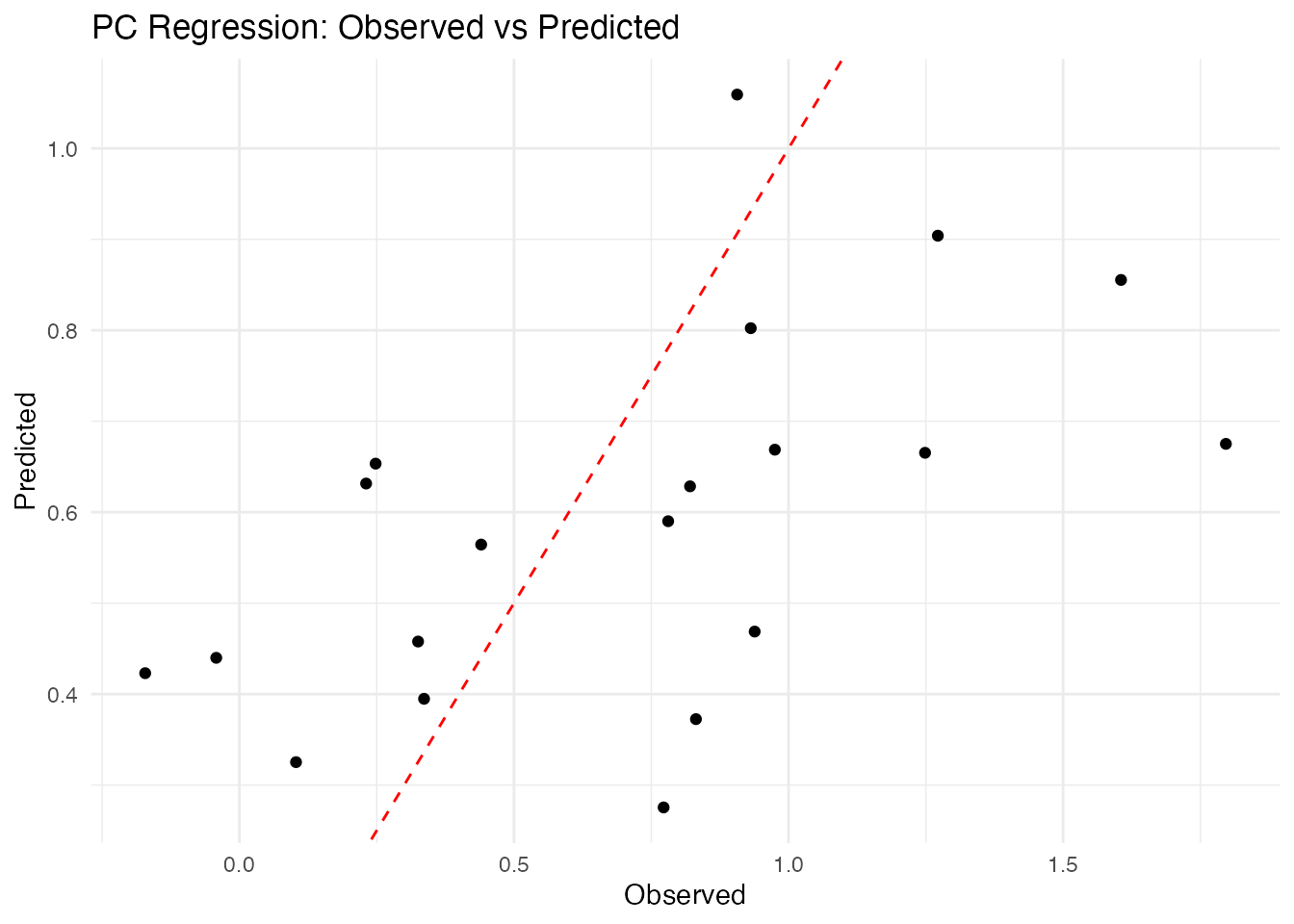

#> 3 k-NN 0.4935318 0.08906132Visualizing Predictions

# Create comparison data frame

df_pred <- data.frame(

Observed = y_test,

PC = pred1,

Basis = pred2,

kNN = pred3

)

# Observed vs predicted

ggplot(df_pred, aes(x = Observed, y = PC)) +

geom_point() +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = 1, linetype = "dashed", color = "red") +

labs(title = "PC Regression: Observed vs Predicted",

x = "Observed", y = "Predicted") +

theme_minimal()

Method Selection Guide

When to Use Each Method

Principal Component Regression

(fregre.pc):

- Best when the functional predictor has clear dominant modes of variation

- Computationally efficient for large datasets

- Interpretable: each PC represents a pattern in the data

- Use when is small relative to the complexity of

Basis Expansion Regression

(fregre.basis):

- Best when you believe is smooth

- Use B-splines for local features, Fourier for periodic patterns

- The penalty parameter provides automatic regularization

- Good when you want to visualize and interpret

Nonparametric Regression

(fregre.np):

- Best when the relationship between and may be nonlinear

- Makes minimal assumptions about the data-generating process

- Computationally more expensive (requires distance calculations)

- May require larger sample sizes for stable estimation

Prediction Metrics

Model performance is evaluated using standard regression metrics. Given observed values and predictions :

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | Average absolute error | |

| MSE | Average squared error | |

| RMSE | Error in original units | |

| Proportion of variance explained |

References

Foundational texts:

- Ramsay, J.O. and Silverman, B.W. (2005). Functional Data Analysis, 2nd ed. Springer.

- Ferraty, F. and Vieu, P. (2006). Nonparametric Functional Data Analysis: Theory and Practice. Springer.

- Horváth, L. and Kokoszka, P. (2012). Inference for Functional Data with Applications. Springer.

Key methodological papers:

- Cardot, H., Ferraty, F., and Sarda, P. (1999). Functional Linear Model. Statistics & Probability Letters, 45(1), 11-22.

- Reiss, P.T. and Ogden, R.T. (2007). Functional Principal Component Regression and Functional Partial Least Squares. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 102(479), 984-996.

- Goldsmith, J., Bobb, J., Crainiceanu, C., Caffo, B., and Reich, D. (2011). Penalized Functional Regression. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 20(4), 830-851.

On nonparametric functional regression:

- Ferraty, F., Laksaci, A., and Vieu, P. (2006). Estimating Some Characteristics of the Conditional Distribution in Nonparametric Functional Models. Statistical Inference for Stochastic Processes, 9, 47-76.